Blood on Satan’s Claw: Genre, Social Control, and Misogyny in Rural Horror

Brief Synopsis: Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), directed by Piers Haggard and produced by Taigon Films, is one of the key films in the subgenre known as folk horror. The story is set in 17th-century rural England, when a young farmer discovers a demonic skull that seems to trigger a series of dark and supernatural events. The village’s children and teenagers become possessed by a malevolent force, driving them to perform pagan and satanic rituals. The film culminates in a witch hunt orchestrated by local authorities, aiming to eradicate this evil.

Social and Gender Context in Folk Horror: Folk horror often explores collective fears related to nature and ancient beliefs clashing with modernity. In Blood on Satan’s Claw, however, this primal terror is also intertwined with issues of gender, power, and social control. The film presents a community that, in its attempt to eliminate what it perceives as a pagan threat, resorts to violence and oppression, especially targeting young women.

One of the main themes of the film is the sexualization and demonization of women, a portrayal that aligns with the long tradition of witch hunts in Europe. Silvia Federici, in her book Caliban and the Witch (2004), argues that witch hunts were not merely a religious phenomenon but also a mechanism of control over the female body during a time of socio-economic change. Blood on Satan’s Claw reflects this by showing how women, particularly young women, are viewed as the source of corruption and depravity, and how their punishment becomes a means of restoring «order.»

The Witch Hunt and the Control of the Female Body: The film opens with a seemingly innocent scene: Ralph, a young farmer, ploughing the fields, discovers skeletal remains that appear to have demonic characteristics. From that moment, a series of strange events unfold, where the village’s youth, especially the women, begin to exhibit sinful and «possessed» behaviour. This shift towards transgression and «immoral» behaviour becomes a reflection of the moral panic that surrounded young women during times of intense sexual and social repression.

In the context of gender, this story evokes the fears historically projected onto women by patriarchal societies. Angela Carter, in her study The Sadeian Woman (1979), describes how female sexuality has often been linked with the demonic or corrupting, with women associated with temptation and sin. The character of Angel Blake, played by Linda Hayden, is a perfect example of this demonization: a young woman who, under the influence of evil, uses her sexuality to manipulate men and lead sacrilegious rituals. In a key scene, Angel seduces the local priest, usurping his moral and religious authority. This subversion of clerical power by a woman reinforces the male fear of losing control over the female body and its reproductive capacity, themes also present in the hysteria of historical witch hunts.

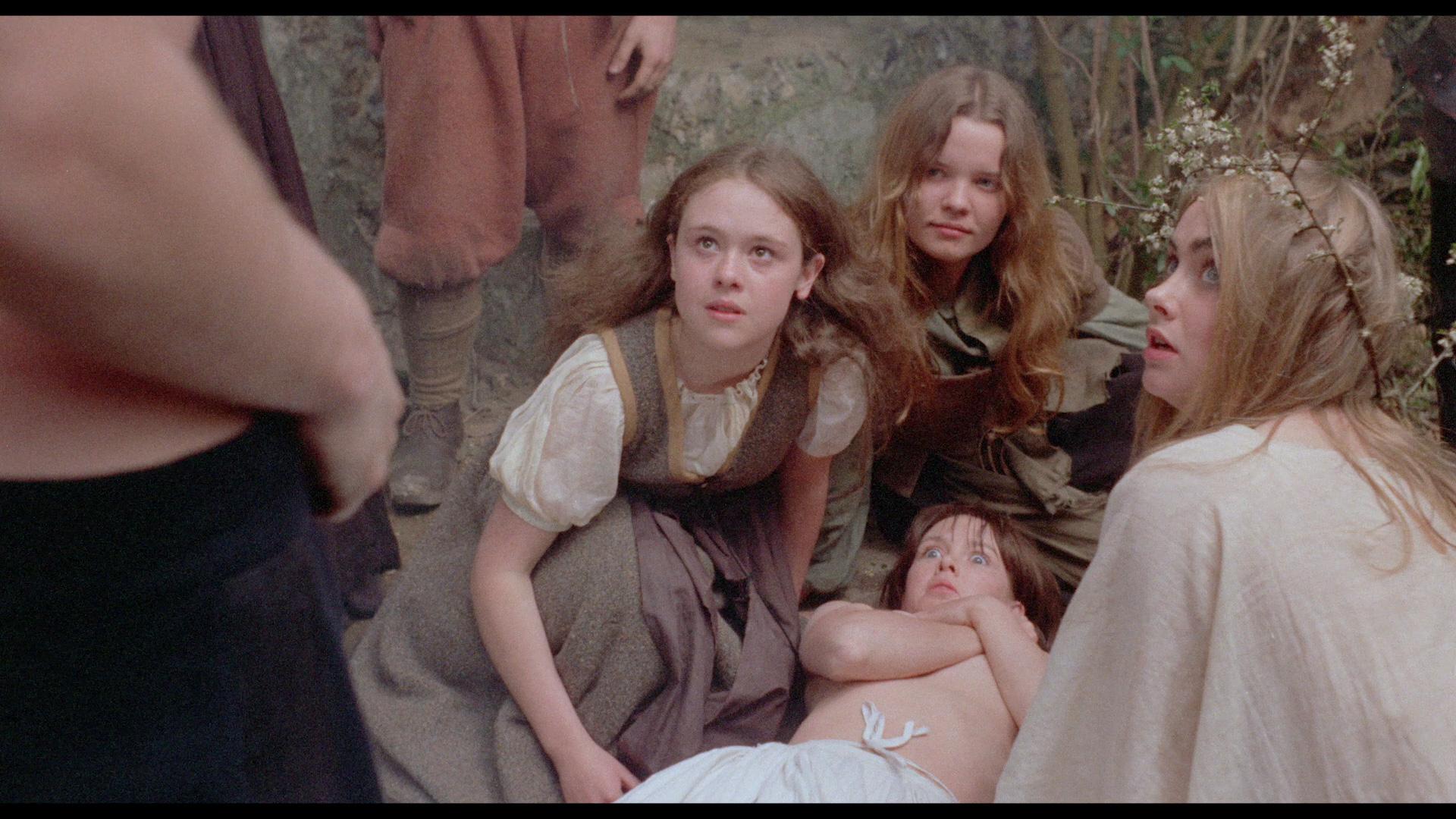

Sexual Violence and Bodily Horror: Another crucial element in the film is how control over women’s bodies is exercised through sexual violence. One of the most shocking scenes occurs when Margaret, a young girl from the village, is pursued and assaulted by a group of men who believe she is «possessed» due to a demonic mark that appears on her skin. This scene is brutal not only for its explicit depiction of violence but for the way it reveals how women’s bodies become battlegrounds between the forces of law and evil.

Federici, in Caliban and the Witch, asserts that the burning of witches was essentially a way to discipline female bodies, especially regarding their sexual autonomy. In Blood on Satan’s Claw, the physical marks of «evil» become excuses for violence against women, particularly young and desirable bodies. The film echoes this idea, as women are not only portrayed as victims of evil but as physical carriers of corruption, justifying the brutality inflicted upon them.

Youth, Sexuality, and Power: The film’s focus is on youth, which is depicted as particularly vulnerable to satanic influence. This is especially evident in the cult led by Angel, where girls and teenagers become the primary followers of the demon. The village adults, especially the men, view this behaviour as a direct threat to the community’s morality and stability, provoking a violent reaction that culminates in acts of torture and death.

Historian Marion Gibson, in her book Witchcraft and Society in England (1999), argues that the persecution of young women during witch trials was often linked to fears of female reproductive and sexual power. This resonates with the narrative of Blood on Satan’s Claw, where young women experiencing sexual awakening are punished under the suspicion of being connected to evil. The presence of the demon serves as a metaphor for female sexuality, which is seen as something that must be controlled and purged.

Religion and Patriarchal Power: In Blood on Satan’s Claw, the church and male authority figures act as forces of oppression seeking to restore social order. Rather than representing a force for good, religion becomes a weapon to subjugate women and the young. This is shown through the character of the judge, who, instead of seeking truth, is more concerned with eradicating evil brutally and mercilessly.

This aspect of the film recalls Michel Foucault’s work Discipline and Punish (1975), where he analyses how institutions of power, such as the church or the state, are structured around the control of bodies. The film suggests that the real horror does not come from the demon itself, but from the way power structures are willing to sacrifice lives to maintain the status quo.

Conclusion: Horror as Social Reflection: Blood on Satan’s Claw is much more than a simple horror film about demonic possession. Through its imagery of sexual violence, social control, and the repression of women, the film becomes a mirror of patriarchal fears and the desire to control female bodies. On a deeper level, the film shows us that horror does not only reside in the supernatural but also in the power structures that suppress freedom, particularly that of young women.